The Great Urdu Divide: Past and Present

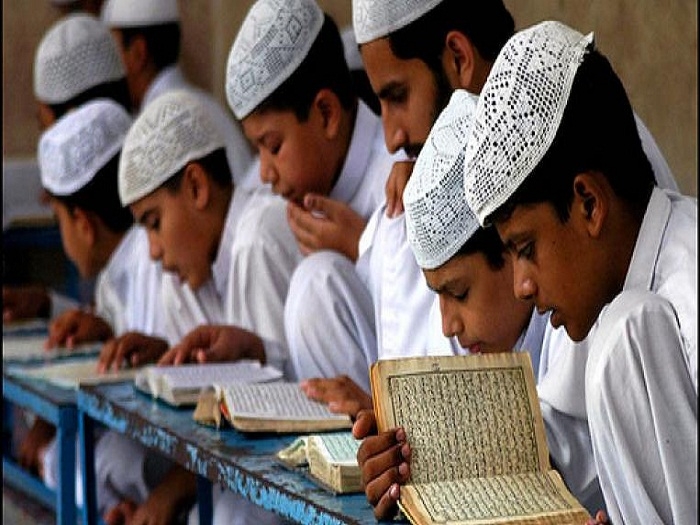

In a strange and inadvertent development, social segregation is taking place in thousands of mainstream schools of North India along religio-linguistic lines. Many schools in north India offer Sanskrit or a regional language or a foreign language as a third language, the first two being the local vernacular and English. Most Muslim students are choosing Urdu as the third language and non-Muslims are avoiding it, and purely for administrative conveniences and operational economy the school authorities are clubbing Muslim students in one separate section. This is happening in both Government and private schools. The result is segregation of the Muslim students from the rest, which is called “ghettoisation of Muslims” by Nazia Erum (2018) who has conducted a survey and given a meaningful and informative analysis. The Muslim students do not get to know their Hindu, Sikh, Christian, fellow students and that obviously is socially divisive and contrary to national integration. Sadly this is happening to Muslims who want to remain in the mainstream and give their children modern education. It is obvious that both Muslims and non-Muslims perceive Urdu as a language exclusively for the Muslims.

A little more than a decade ago in August 2004 an ordinance was brought to set up an Urdu University in Rampur, in western Uttar Pradesh, under the ‘permanent custodianship’ of M. Azam Khan, the Urban Development Minister in the then Samajvadi Party government of Uttar Pradesh. Azam Khan promptly declared that the syllabus of the university would be ‘copied’ from the Al-Azhar University of Cairo, Egypt. This showed up the extra-territorial mooring of the Urdu language once again and in a brazen fashion. The ordinance was referred to the President by the Governor and the former returned it and asked the Governor to seek legal opinion. Thus thwarted the ruling party passed a bill to set up the Urdu university in the private sector. I am not aware of its current status. But what I am aware is that both the President and the Governor were treading cautiously for the socially divisive nature of the proposal.

Origin of Urdu: There are some obvious relevant questions. How did Urdu acquire an extra-territorial mooring? How it came to be perceived as the language of the Muslims? What were the consequences? It would be pertinent to explore the origin of Urdu. The descendants of the Muslim invaders who settled around Delhi acquired the lingua franca of the region, Khadi Boli, to which they added a sprinkling of their own vocabulary. Khadi Boli had reached the Deccan even earlier through trade, Sufi-Bhakti saints, and invading Muslim armies from North India, but the decision of Mohammad Bin Tughlaq to shift his capital to Daulatabad in Deccan (1327 AD) led to a substantial shift of population from Delhi region to Deccan and brought Khadi Boli (also known as Hindavi) to Deccan in a very big way. Ramdhari Singh Dinkar (1956), among others like Suniti Kumar Chatterji and R.S. McGregor, holds that it was Hindavi of North that started being written in the Arabic (Nastaliq) script in the Deccan and at that moment Dakhni-Urdu was born. Noted Pakistani author Iqbal Khan (1987) in his ‘Rise of Urdu and Partition’ writes:

The Hindawi of the north...became the language of administration and transaction in the Bahmani kingdom. From this evolved the Dakhni language or the Urdu of Deccan.

It was transformed into an artificial Arabised-Persianised language with extra-territorial mooring in the later part of the Mogul era. We shall discuss more about it later. One of the Bahamani rulers Ibrahim Adil Shah himself was a poet and translated a part of the Natya Shastra, a treatise on dramatics written in Sanskrit, and titled it Nauras Nama, refering to the nine Rasas of the Natya Shastra. In invocation to God Ganesha he wrote,

Saaradaa Ganesh maataa pitaa/ Tum Mano nirmal beeb sphatik.

(Saraswati and Ganesh are (like) mother and father/ you are like transparent crystals.)

Here the title Nauras Nama is a mixture of Sanskrit and Persian, and the poetry is rich in Sanskritic words. The language reflects the composite culture of the Adil Shahi times. To begin with poet Wali Dakhni wrote in Dakhni-Urdu or Deccan-Urdu [Dinkar, p. 385].

But an event happened during Wali’s lifetime that changed the character of Urdu and influenced the future course of Indian history. In 1686 AD Aurangzeb decided to establish in Aurangabad (in present Maharashtra) his center for the long drawn Deccan wars. Now the Northern establishment came in prolonged contact with Dakhini-Urdu. Wali himself visited Delhi twice (1690 AD and 1724 AD), where he impressed the Mogul court with his poetry. It is now necessary to trace the evolution of the atmosphere of the Mogul court since Akbar’s liberal times. Iqbal Khan (1987) says,

“As a result of Mongol (Mogul) invasion of central Asia, large numbers of the Ulema (priests, theologians) migrated to India. They were followers of the Sunni faith and in matters of Fiqh held extremist views. On arriving here they compelled the Sultans of Delhi not to treat Hindus as Zimmis, because that treatment is permissible only towards the people of the Book (Koran).”

There was a long drawn tussle between the liberal and the orthodox elements in the Mogul court. Naqshbandiyya Sufi order of Sirhind opposed Akbar’s liberal policies. Abul Fazal, Akbar’s court historian, author of Ain-I-Akbari and translator of Bhagavad Geeta, was murdered. The struggle continued through the reign of Jahangir and Shah Jahan. The orthodoxy opposed Dara Shikoh’s claim to the throne and backed Aurangzeb. Later he became a murid (disciple) of Shekh Saifuddin Sirhindi of the Naqshbandiyya order. In Iqbal khan' s (1987) words,

“The orthodox elements’ final triumph came with the ascension of Aurangzeb to the throne….Islamic fundamentalism and reaction now reigned supreme. It was in this atmosphere that Urdu arrived in Delhi in the person of poet Wali Dakhni. Urdu was literally usurped by the ruling classes and reshaped….All that was genuinely Indian in its make-up was suppressed…. It now emerged as the language of the Muslim….”

The orthodoxy looked down upon the Indian Khadi boli or Braj as the language of the infidel and was pro-Persian in language policy. At the same time they realized that Persian can never become a popular language in India. They took interest in Wali Dakhni’s works because they saw in it the successful adaptation of a local language that would lend itself to Persianization and can be a vehicle of orthodox thoughts [Dinkar 1956, p. 386]. There Shah Gulshan, an elderly and respectable poet of Persian, advised Wali to use Persian words in his works. Wali followed the advice and started excluding vernacular words and replacing them with Persian ones. But he was not completely successful as shown by Dinkar (ibid), who has quoted a verse written by Wali, after his transformation. There was a similar attempt by Faiz, one of the earliest Urdu poets of the North and a contemporary of Wali, to Persianize the vernacular but he too could not write consistently in that artificial medium [Dinkar 1956, p. 386].

The Policy of Expulsion or Matrukaat ya Bahishkaar ki Niti: Hence the pronouns, verbs, the syntax and grammar of the vernacular had to be retained in good measure. The nouns, adjectives, idioms and metaphors of Indian origin were sought to be expelled as far as possible. Dinkar calls this policy “Matrukaat ya Bahishkaar ki Niti” [Dinkar 1956, p. 385]. It should be noted that Persian of the Mogul era had already been thoroughly Arabized in the prior six centuries of its post-Islamic phase during Arab rule. So in effect the process of Persianization resulted in Persio-Arabization of Urdu. Dakhni-Urduhad acquired some Telugu, Marathi and Gujrati influences. All these were systematically purged along with the Sanskritic ones. Thus emerged the northern Urdu, which is the present form of Urdu, from the womb of Dakhni-Urdu. Though Urdu is a language of North India, it has acquired so much of a foreign character that the present author, who lived in Uttar Pradesh and read and speak fluently Hindi, the local language, cannot follow the Urdu news bulletins issued by Lucknow Door Darshan. The irony is that even a common Muslim who is not specially trained in Urdu cannot understand the bulletins either. The present author can however easily understand the colloquial language of the common Muslim which is no different from the speech of the common Hindu, and this colloquial language is not so heavily loaded with Persio-Arabic words as the formal Urdu news bulletin.

Returning to the theme of the great Urdu divide, Iqbal Khan (1987) holds Urdu as responsible for the partition of the country in 1947 and squarely blames the Muslim fundamentalists. However, he makes no attempt to explain the fact that neither Jinnah nor Liaqat Ali Khan nor poet Iqbal nor any of the leading lights of the Two-Nation-Theory was a fundamentalist.

Linguistic Exclusion Principle: Loyalty to a language and its script is often an important ingredient of nationalism. Therefore a religion-inspired nationalist seeks to restrict language and literature artificially so as to serve the narrow purpose of his own religious community. At the same time he attempts to exclude other people who are adherents of other religions but inhabit the same geographical area or land; this is a kind of Linguistic Exclusion Principle applied in the sphere of religion, which will be denoted in abbreviation by LEP hereafter.

The Two Nation Theory, which holds that Muslims and Hindus are two separate nations and which led to the partition of India in 1947, belongs to the category of religion-inspired nationalism. Moreover, the Urdu language, which had been nurtured on the Linguistic Exclusion Principle (LEP) in the preceding centuries, had an important role in the growth of the Two-Nation-Theory.

The Process: To start with there is a religious community which has a tendency to impose the script of its scripture on a language unrelated to the scripture. Thereafter the process starts and develops in three phases. In the first phase, the fundamentalist clergy (Ulema) and the sectarian Sufi (such as the Naqshbandiyya) provide inspiration for the separate sectarian identity to the “people of the book” (zimmi). A pitched battle starts between the sectarians and the liberals within the religious community. Sectarians are better organized and scatter the liberals easily. Political formations take shape which reflects the victory of the sectarians, and the attitude towards the people of other faiths hardens.

This leads, in the second phase, to the creation of an artificial language, such as the post-Aurangzeb form of Urdu. For example, poet Mirza Ghalib employs eight metaphors to describe something as typically Indian as a roasted betel nut and yet seven out of eight metaphors are foreign (Khan 1987). Sanskrit/Dravidian nouns, adjectives and phrases are replaced by Arbi/Farsi ones. In Khan’s (1987) words,

“…All that was genuinely Indian in its make up…. was suppressed and purged from it (Urdu)”.

Here we see the Linguistic Exclusion Principle in full flow. Hindus are sought to be excluded from the language and its literature, and Urdu emerges as the language of the Muslim. This phase of creation of an artificial language and a sectarian culture spans centuries.

In the third phase the LEP which remains quietly at work in a subterranean fashion succeeds in creating a sectarian nationalist identity which now infects even those members of the community who are modern and reformist and even areligious and non-believers at times. There is a gap of centuries between the initial inspiration provided by the fundamentalist and the modernist intellectuals falling prey to a socially divisive culture. Famous personalities like M. A. Jinnah, poet Iqbal and Liaqat Ali Khan are such modernist intellectuals who are responsible for India’s partition. At that turning point in time they are not aware of the historical process that has shaped their attitude. They oppose fundamentalism in the name of modernism, but glorify a sectarian form of Muslim nationalism in the garb of the Two-Nation-Theory. Thus religious fundamentalism gave birth to the Two-Nation-Theory through a long-drawn process in which the LEP played the role of a midwife, and it is obvious that the Two-Nation-Theory influenced both the fundamentalist and the modernist alike.

The present: What is sad is that even after the cathartic and horrendous events of partition of the country the influence of the Urdu language persists in a greater part of India. We allowed it the status of a second language in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, and now Mamata Banerjee, the Chief Minister of W. Bengal, has done likewise succumbing to the demand of the Urdu-speaking people who are a small minority among the Muslims of Bengal. We did not accord the rightful place to the vernacular Kashmiri in Kashmir, and allowed Urdu to be the medium of administration and education even in the primary schools.

The present highly-Arabized form of Urdu is being further morphed by the orthodox elements. Persian words are gradually being supplanted by Arabic words as per the dictates of a section of the Sunni clergy. For instance, there is a campaign to replace ‘Namaaz’ by ‘Ibaadat’, both meaning prayer. The first is Persian and the second Arabic. Likewise, Khuda, a word for God in Persian is sought to be replaced by Allah; and the much used phrase Khuda Hafiz, spoken at the time of parting company, is gradually giving way to Allah Hafiz. The Shia community is not averse to retaining Persian words owing to their fondness for the leading Shia state, Iran, whose older name was Persia. Thus Shia Urdu and Sunni Urdu are slowly drifting apart, which would again divide the society further.

Conclusion: When two religious communities live side by side and yet read different newspapers, magazines and literature, they grow culturally apart. The existing religious divide becomes an unbridgeable multi-dimensional cultural divide. After all, that exactly was the purpose behind the policy of ‘Matrukaat’,meaning Bhishkaar, that shaped Urdu since the times of Mogul emperor Aurangzeb. British sociologists have recognized a similar trend among Muslim immigrants and their descendants in Europe and called it a policy of ‘Voluntary Apartheid’. Anyone who has experienced the relationships between Muslims and Hindus both in Uttar Pradesh and W. Bengal can perceive the contrast. In Bengal the religious division exists, but is to a great extent bridged by the common newspapers, magazines and literature; school children are not segregated in different sections along religious lines in modern schools. This author has lived in Uttar Pradesh, W. Bengal and Hyderabad the capital city of erstwhile Andhra Pradesh and present Telangana. He was surprised to come across this cultural divide also in Hyderabad, between Urdu-speaking Muslims and Telugu people, which is perhaps even stronger than that of Uttar Pradesh. An Urdu-speaking Muslim upper class gentleman - there is a very large such class in Hyderabad - is ashamed of speaking Telugu even if he can actually speak. In a town of Uttar Pradesh the Hindus and Muslims are happy to share a common spoken tongue. I have heard that a similar division as in Hyderabad exists in Karnataka and northern Tamil Nadu as well, but in a subdued form because the Muslim elite there is not so numerous and dominant. What is, however, alarming is that in the two Muslim-majority districts of northern Kerala, much in the news for terrorist activities, there is an organized effort to import Urdu from the north.

The policy makers of school education should recognize the problem of Ghettoization of Muslims, to which Erum (2018) has drawn attention, and search for a remedy. The government should issue a regulation that Muslim children must not be ‘ghettoized’; instead they should be distributed more or less evenly among non-Muslim students in all sections in a modern school, private or public. Also, since Urdu has once acted as an agent of the partition of the country, so to speak, there should be a public debate on whether it should be accorded the status of an official language in any state other than Jammu & Kashmir.

References

‘Dinkar’, Ramdhari Singh (1956): Sanskrti Ke Char Adhyaya (with a foreword by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru), Lok Bharati Prakashan (Allahabad, 2002).

Erum, Nazia (2018): Divide and School Policy Ghettoising Muslim Kids, The Sunday Times, Times of India Publications, New Delhi, Ahmedabad, p. 12, January 7.

Khan, Iqbal (1987): Rise of Urdu and Partition, Viewpoint, July-Sep, Lahore, Pakistan; reprinted in Times of India, Oct 2,3&5, 1987 as one of the series to mark 40 years of independence. (Iqbal Khan is a author and journalist.)