Swami Vivekananda’s Chicago Address: A message to humanity

a

a

Six years ago on January 28, 2013 commemorating the 150th anniversary of Swami Vivekannda’s address to the World Parliament of Religions, the British Parliament unanimously passed a resolution recognizing the Swami’s contribution in initiating the interfaith dialogue at international level, encouraging and promoting harmony and understanding between religions through his renowned lecture.

The resolution also acknowledged and endorsed the fact that Swamiji’s lectures in the West “rectified and improved the understanding of the Hindu faith outside India and dwelt upon the universal goodness found within all religions”.

The credit for this opening the minds and expanding moral imagination of the West must go unquestioningly and undoubtedly to one and the only one Swami Vivekananda. It was he who played a historic role in placing the jewels of the ancient Hindu thought before the West and thus helped them in widening the dimensions and depth of their moral imagination.

While analysing the visit of Swami Vivekananda to the World Parliament of Religions it is necessary to ponder over the following facts: Firstly, he was not sent there by an independent India because the country was reeling under the yoke of British slavery. Secondly, he was not sent as an official representative of any Indian religious authority or organization, because Indian spiritual tradition simply do not permit the single central powerful authority or church like the Semitic religions. He encountered difficulties at the time of admission to the Parliament of Religions in America later. The Swami went to the Parliament of Religions as a representative of the expanding spiritual consciousness of India in its fullness, through the instrumentality of a group of nationally sensitive Indian people.

The purpose and purport of the Parliament of Religions: The emergence of the USA as global power due to tremendous progress made by the nation in science and technology and phenomenal increase in its national wealth prompted the Americans to celebrate this in a befitting manner. It was a happy coincidence that quadric-centenary of America’s discovery by Christopher Columbus was approaching. The citizens of Chicago, the second largest city after New York, decided to grab this opportunity by organizing the Columbian Exposition and World’s Fair on the lines of the first such fair held in Hyde Park, London in 1851 commemorating Queen Victoria’s silver jubilee; and the Paris exhibition of 1889 when the Eiffel Tower was first opened to the public view. The Columbian Exposition and World’s Fair, the Americans thought, would surpass these earlier two events.

One Mr Charles Bonney, who was a famous lawyer and social activist, had suggested to include religion as one of the themes of the World’s Fair and when his suggestion was accepted he conceived of a World’s Parliament of Religions, in which representatives of all the principal religions of the world would be brought together.

This idea found acceptance and Rev. John Henry Barrows, Pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago was appointed Chairman of the General Committee. Mr Bonney’s original idea in organizing this Parliament was to prove the supremacy of Christian faith in the world. Swami Vivekananda had expressed his admiration for this Mr Bonney in a letter to the Maharaja of Khetri. The Swami wrote, “Mr Bonney is such a wonderful man! Think of that mind that planned and carried out with great success that gigantic undertaking, and he is no clergyman, a lawyer presiding over the dignitaries of all the churches—the sweet, learned patient Mr Bonney with all his soul speaking through his bright eyes.”

However, Mr Bonney later regretted his dream of religious fraternity. The Baltimore Sun of October 11, 1894 carried an article with a title, “The Christian Religion—President Bonney says that The Parliament of Religions Will Make it Supreme”.

However, the mask Rev Barrows put on before and during the Parliament completely fell afterwards the praise Swami Vivekananda showered on him notwithstanding. All the fame that he had earned for successfully organizing the Parliament was lost, so far as India was concerned. In 1897 he came to India to preach Gospel and he preached “the most bigoted Christianity, with the result that nobody listened to him”, mentioned Swami Vivekananda in his letter to Mary Hale on April 28, 1897.

Swami sails for Chicago: Swami Vivekananda sailed for Chicago on May 31, 1893 from Bombay and passing through Colombo, Penang, Singapore, Hong Kong, Canton, Nagasaki, Kobe, Osaka, Kyoto, Tokyo and Yokohama, landed at Vancouver from where he travelled to Chicago by train in the middle of July 1893. From then to his first historic speech at the parliament of religions in 11th September 1893, he had to face many hardships and sharp moments of despair. The Life describes his difficulties thus: “Burdened with unaccustomed possessions, not knowing where to go, conspicuous because of his strange attire, annoyed by the lads who ran after him in amusement, weary and confused by the exorbitant charges of the porters, bewildered by the crowds, chiefly visitors to and from the World’s Fair, he sought a hotel. When the porters had brought his luggage and he was at last alone and free from interruptions, he sat down amidst his trunks and satches and tried to calm his mind”.

The Swami reached America towards the end of July 1893. He was shocked to know from the organizers that the Parliament was scheduled to be held in September and no one would be admitted as a delegate without valid credentials issued by the recognized religious organization or church. He had no such letter with him that would prove him as representative of Hinduism nor had he sufficient money to sustain himself till the Parliament began. Therefore, his sojourn in America was an extension of his wandering days, with kind Providence alone as his support. But he overcame all the difficulties in providential ways.

On his way to Boston, he became acquainted with Miss Kate Sanborn, an influential lady who invited him to stay at her beautiful house called “Breezy Meadows” in Metcalf, Massachusetts. She introduced him to Prof John H Wright, Professor of Greek at the Harvard University. Prof Wright was very much impressed by Swami Vivekananda during the four hour long conversation he had with him. The Professor insisted that he should represent Hinduism in the parliament. When the Swami expressed his difficulty in attending the Parliament for want of credentials, Prof Wright made a remark: “To ask you, Swami for your credentials is like asking the Sun to state its right to shine”. He immediately wrote a letter to the Chairman of the Parliament Rev. Barrows introducing Swami Vivekananda as “Here is a man who is more learned than all our learned professors put together”.

Prof Wright also provided the journey ticket to Swami Vivekananda to Chicago. When the Swami reached Chicago to his disgust he found that he lost the address of the office of the Parliament. He being a coloured man, no one helped him either. He walked along the road until he was quite tired. He found an empty boxcar at Railway yard and used it as his night shelter in that cold night.

Difficulties at Chicago: In the morning he got up and walking some distance, found himself in a modern area of the city. Tired and hungry, he begged for food and shelter at several houses only to be rudely rebuffed. At last, resigning himself to the Divine Will, he sat on the roadside. Just then a miracle happened as if well planned by the Divine power. From a fashionable house opposite where the Swami was sitting, there emerged a tall, regal-looking lady who approached him and politely enquired whether he had come for the Parliament as Oriental delegate. When the Swami answered in affirmative, she offered him to take to the office of the Parliament and invited him to her house for a breakfast. This kind lady was Mrs. George W Hale. This marked the beginning of Swami Vivekananda’s friendship with the Hale family. During his stay at America, their home was the centre from which he moved in different parts of the United States. Mrs Hale took the Swami to the office of the Parliament where after submitting his credentials, he was admitted as a delegate and places with the other Oriental delegates.

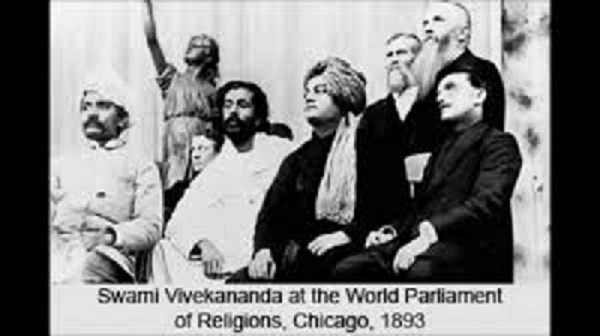

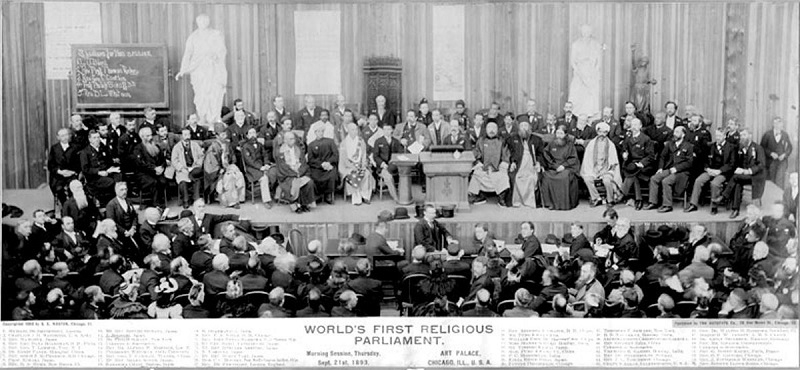

The Parliament of Religions opened on Monday, 11th September 1893 at the Art Institute building in presence of four thousand men and women who had gathered in the Hall of Columbus and the hundreds were standing in the galleries and doorways in breathless silence and in the mood of tense expectancy. The ten principal religions—Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Zoroastrianism, Catholicism and Protestantism—participated in the Parliament which began at the stroke of 10 am on that appointed historic day. Cardinal Gibbons, the highest dignitary of the Roman Catholic Church in America occupied the central seat. All the delegates were dressed in their respective appropriate apparels—Swami Vivekananda was conspicuous amongst all the delegates with his gorgeous red apparel and a yellow turban. Cardinal Gibbons wore crimson robes while Buddhists were in white, the Greeks in black garbs, Confucian in the dress of a mandarin, a young African prince in his richly embroidered robes.

The Historic Speech: After the initial prayer of the Lord “Our Father who art in Heaven.....”, the proceedings of the Parliament began. Swami Vivekananda sat rapt in silent meditation. Every time the Chairman called his name he would say, “no, not yet”. At last the Chairman insisted forcing the Swami to rise to speak. He bowed to Goddess Saraswati and began his speech with addressing the audience as “Sisters and Brothers of America”. And that worked like a magic spell! Before he could utter another word, the entire audience enthusiastically responded to him rising to their feet and sending deafening notes of applause over and over again. For full two minutes he attempted to speak but the wild enthusiasm and applause of the masses did not allow him to proceed. This thunderous applause instantaneously recognized that his thinking was different from the others. This was like heralding the advent of a new prophet!

Praises shower from all corners: A representative reaction of one American lady who attended the Parliament would suffice to state the impact of those five words of Swami Vivekananda on the minds of the audience. Mrs. S K Blodgett, who later became Swami Vivekananda’s hostess in Los Angeles during his second visit to America, was among the crowd that greeted the Swami most vociferously on that day in the Parliament. Recalling the event a few years later, she told Miss MacLeod, “If ever there was a God on earth, that is the man”, pointing to a full size portrait of Swami Vivekananda on the wall. Mrs. Blodgett said, “When that young man got up and said, Sisters and Borthers of America, seven thousand people rose to their feet as a tribute to something they knew not what.”

The Life says “But here was a soul, greeting thousands of other souls by sweet and loving terms, Sisters and Brothers… Was it this, or was it the Divine Power behind him that had seized the audience by a whirlpool of spiritual ecstasy—for it was nothing short of ecstasy”.

Swami Ranganathananda later described the event in this way: “It was a brief but intense speech. Its spirit of universality, earnestness, and breadth of outlook completely captivated the whole assembly. He cast off the formalism of the Parliament and spoke to the people in the language of the heart. The phrase of five words which he initially uttered ‘Sisters and Brothers of America’, was a tongue of flame which sets aflame the hearts of his listeners. Each orator has spoken of his God, of the God of his sect. He alone spoke on behalf of their Gods, and embraced them all in the Universal Being. It was the spirit of Sri Ramakrishna breaking down the barriers between religions through the voice of his great disciple.”

The Parliament met thrice daily for seventeen days and a tremendous amount of business was transacted during this time in different sessions. During these sessions the Swami spoke on ‘Why We Disagree’ on September 15, denouncing the insularity of religions by quoting the famous parable of ‘Frog in the Well’. He read his famous paper on ‘Hinduism’ in September 19, followed by a talk on ‘Religion not the crying need of India’ on the next day. Here he exhorted the Christian nations not to waste their resources and energy in converting and saving the souls of the heathens, but to concentrate on saving their hungry bodies. He also delivered lectures on ‘Orthodox Hinduism and the Vedanta Philosophy’, and ‘The Modern Religions of India’ on September 23, ‘The essence of Hindu religion’ on September 25, on ‘Buddhism the fulfilment of Hinduism’ on September 26 and delivered his address at the final session of the Parliament on September 27.

The spirit of his address: Sister Nivedita has caught the spirit of his addresses. In her introduction to the Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda says, “Of the Swami’s address before the Parliament of Religions, it may be said that when he began to speak, it was the religious ideas of Hindus; but when he ended Hinduism had been created. …For it was no experience of his own that rose to the lips of Swami Vivekananda there. He did not even take advantage of the occasion to tell the story of his Master. Instead of either of these, it was the religious consciousness of India that spoke through him, the message of his whole people, as determined by their whole past. And as he spoke in the youth and noonday of West, a nation sleeping in the shadows of the darkened half of the earth, on the far side of the Pacific, waited in spirit of the words that would be borne on the dawn that was traveling towards them, to reveal to them the secret of their own greatness and strength.”

From the first speech he delivered at the Parliament of Religions to August 1895 when he set sail to England en route India, Swami Vivekananda had a hectic time in the United States. He was the star of attraction of the American people and media. The important daily papers of Chicago—The Chicago Daily Tribune, and the Chicago Daily News, the Boston Evening Transcript, The Review of Reviews, were all praise for him. The Boston Evening Transcript wrote, “He is a great favorite at the Parliament from the grandeur of his sentiments and his appearances as well. If he merely crossed the platform, he is applauded; and this marked approval of thousand he accepts in a child-like spirit of gratification without a trace of conceit……” The Review of Reviews described his address as ‘noble and sublime’

But the Parliament witnessed some moments of sharp criticism and attack on Hindus by the Christian speakers who did not took well the praise being showered on Swami Vivekananda. The Dubuque Iowa Times of September 20, 1893 reported, “The day began with a sharp attack on Hindus by Rev. Joseph Cook and other divines, which was followed by replies from the ‘three learned Buddhists’. According to the paper, “Swami Vivekananda, the Hindoo monk, was not so fortunate. He was out of humor, or soon became so, apparently. He wore an orange robe and a pale yellow turban and dashed at once into a savage attack on Christian nations in these words: "We who have come from the east have sat here day after day and have been told in a patronizing way that we ought to accept Christianity because Christian nations are the most prosperous. We look about us and we see England the most prosperous Christian nation in the world, with her foot on the neck of 250,000,000 Asiatic. We look back into history and see that the prosperity of Christian Europe began with Spain. Spain's prosperity began with the invasion of Mexico. Christianity wins its prosperity by cutting the throats of its fellow men. At such a price the Hindoo will not have prosperity." And so they went on, each succeeding speaker getting more cantankerous, as it were.” (Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Vol 3)

Eleanor Stark, a noted American academician made this observation summarizing the tremendous impact and the magic spell of Swami Vivekananda’s visit to America. He says: “There was an advent on the American scene of a voice from the East which, in a few short years, sowed the seeds of a regeneration of a great people. At the turn of the century, an unheralded and quiet revolution took place across the land. A message was given by Vivekananda to the American people in words of such universal wisdom and power that those who heard him at the time found their lives changed and their spirits freed. It was a message of humanism in depth, a ringing declaration of a science of human development that did not deny but deepened to new dimensions America’s achievements in science and humanistic philosophy. It was not a call to a new religion but to a new of thinking about religion; not a call to an emotional revival as catharsis for fear and insecurity, but a call to a universal science of spiritual life that affirmed man as God and asked him to look within, to turn inward in order to discover the ground of his Being, and there to discover the same ground in all”. (Eleanor Stark: The Gift Unopened, Pp xix to xx)

Swami Ranganathananada says the intensity of his nine years of mission in the West and in India, the output of spiritual, intellectual, literary and organizational work, besides the traveling involved during the period, was unprecedented. He was the man with a message and he delivered it fearlessly and intensely. He said to himself: “Buddha had a message to the East; and I have a message to the West.”