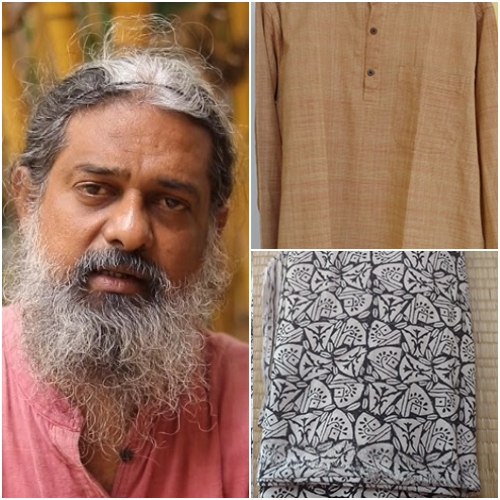

Weaving threads of sustainability! Ananthoo, founder-volunteer of Chennai-based ‘Tula’ highlights value of environment

Total Views |

- Harshad Tulpule

Are the clothes we wear ‘eco-friendly’? Do we think of the environment while selecting a cloth from a store? This is an exclusive interview of Ananthoo, the founder-volunteer of Chennai-based ‘Tula’, a social enterprise which deals in the production and marketing of ‘100% sustainable’ clothes. The interview highlights a very crucial but usually neglected aspect of environment conservation.

What do we mean by ‘eco-friendly’ or ‘sustainable’ clothes? Why are the clothes produced and marketed by Tula ‘100% eco-friendly’?

To determine whether a commodity is eco-friendly or not, we need to make its entire ‘life-cycle-analysis’. Is the garment we use made of cotton fabric or synthetic fibers like nylon? If it is cotton, is it grown organically or chemically? Is the seed used for cotton natural or genetically modified? Is the process of spinning and weaving manual or automated? Are the colors used in the clothes natural or chemical? All these criteria determine whether a garment is eco-friendly or not. The clothes sold by Tula are made of 100% cotton yarn. The cotton used for this is of traditional varieties and is grown organically. The whole process of making cloth is based on human power. No electrical appliances are used. The colors used in the fabric are completely natural. They are made from plants like Palas, Shankhapuspi, Aparajita, Turmeric, Manjistha, etc. The buttons are also made from coconut shells. So even after being used and discarded at its end of life, the whole garment is naturally degradable. Thus, the principles of sustainability are followed in each step, right from the cultivation of cotton to the manufacture of garments and its afterlife. This is why a garment available at Tula is '100% eco-friendly'. There are hardly few such enterprises maintaining such sustainability in the entire value chain of the product. Even in the case of handlooms, the cotton used might not be organically grown!

Today, people are quite aware of plastic-pollution, but there is a lack of awareness about synthetic fibers. What are the environmental hazards of using synthetic yarns?

There is not much difference between plastic and synthetic yarns. Plastic is a petroleum product and widely used synthetic yarns such as nylon, acrylic, polyester are also made from crude oil. The huge pollution that occurs in the process of oil extraction and refining is well-known. More importantly, what happens once a garment becomes useless? The waste it produces is as harmful as plastic! It is now a universally accepted fact that acrylic is carcinogenic. Synthetic yarns don’t decompose naturally. Mixing of microfibers into oceans and water bodies on a mass scale has become a global concern.

We would like to know in brief about India’s heritage of traditional cotton seeds and traditional farming practices. What is their status today?

In India, not only cotton, but of all crops, there was a huge splendor of indigenous varieties. It was destroyed with the commercialization of agriculture. Cotton is a plant of the genus Gossypium, and the world's most widely grown cotton consists of four main species: G. arboreum, G. herbaceum, G. hirsutum, and G. Barbadens. Out of these, Arborium and Herbaceum are the traditional species in India. As cotton has been grown all over India since ancient times, the local varieties were innumerable. Some recent studies have found the existence of colored cotton species in some remote areas. At the time of independence, 92% of India’s total cotton production was from native varieties. 'Dhaka Malmal', an India-made fabric from indigenous varieties, was world famous. The factual details of this heritage are mentioned in the book 'Empire of Cotton: A Global History' by the well-known American historian Sven Beckert. There was no monocropping of cotton at all. Farmers used to grow 10 to 15 different crops including cotton, sorghum, pulses, vegetables, maize, etc. in the same field. In such a cropping pattern, automatic pest control was achieved and the requirement of water was also quite low. These indigenous varieties had the ability to withstand various changes in the climate. Therefore, it is wrong to look at it only from only one point of view i.e. they were 'low-yielding'. The non-monetary and qualitative benefits of such systems have never been taken into account!

Today, most farmers in India grow genetically modified Bt-cotton. Why do you think that this is not a sustainable practice?

There is no doubt that Bt technology has led to an increase in cotton production. But is it fair to measure the results in one single parameter? What about its social and environmental impacts? Bt-cotton has been cultivated in India since 2002. These seeds were brought to India just to serve the commercial interests of powerful American companies like Monsanto. Today, 96% of farmers in India use genetically modified Bt-seeds. The direct and the most disastrous impact was the loss of traditional cotton varieties. We have lost them forever! Traditional biodiversity-rich farms have become factories of producing only cotton! Today, cotton is grown on only 5% of India's land, but more than 50 per cent of the pesticides sold in India are consumed by cotton farms. Farmers lost seed-sovereignty, and every year they are forced to buy seeds from companies because one cannot save the seeds from the Bt cotton plants for next season. The ‘Bollgard worm’, for the prevention of which, a gene from Bacillus thuringiensis (a soil bacteria which controls these boll worms) was introduced, has well adapted to it and farmers are still having to apply heavy doses of pesticides for the prevention of the same. Meanwhile, these boll worms have developed resistance to these Bt and also many other secondary pests started attacking cotton crops. As a result, farmers are becoming poorer and poorer whereas the seed, fertilizer and pesticide companies are getting richer and richer!

After knowing this background, we would like to know in brief about ‘Tula’. When and how was it founded? Today, why Tula is a unique kind of enterprise?

In 2014, our group of 15 friends made an investment of one lakh each to make Rs. 15 lakh with an aim to establish a social enterprise for the marketing of eco-friendly garments. Currently, we are functional in three states - Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. We do not have our own factory or textile mill, but we process it through the different small groups and sell the eco-friendly garments produced by small handloom spinners & weavers. We have enabled some farmers to grow cotton in a traditional way with traditional seeds and have linked them to these weavers. In the early stages, getting the traditional seeds was a big challenge for us. We had to travel to the remote areas in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, talk to many farmers, get traditional seeds from them, study their properties, and apply them in cultivation. A scientist from the Agricultural University also helped us to explore the traditional varieties. Currently, we are a 'social enterprise' working on the principle of 'no-profit-no-loss'. When a customer buys a cloth from us worth Rs.1000, Rs.110 goes in the hands of the farmer, Rs. 130 to the spinner and Rs. 220 to the weaver, rest to dyer, tailor etc. Today, through our enterprise, around 300 people have got livelihood opportunities out of which 100 farmers have started cultivating cotton in a traditional way. We are getting a good response from customers. We also try to reach customers through our own website and through online marketing platforms like India Handmade Collective (https://www.indiahandmadecollective.com/). However, we have followed the principle of selling our goods only in the domestic market but not exporting them.

Is it possible to spread this movement all across India? Do you think that the government should take some steps for this?

It is not impossible, but for that we need to change our concepts of economic growth and our business models. Today, the textile industry in India is monopolized by certain companies. There is fierce competition among companies to capture the global market. Export has become the main objective. You can’t even think of ensuring environmental sustainability in this kind of economic model. For ensuring sustainability we have no option but to go for decentralized small-scale industries where meeting local demands will be the highest priority. I am sure that governments will not encourage this kind of economic model as any government’s main motto is to serve the interests of the big corporates. Even though 'Tula' is a small organization today, we don't want to be big. We have set an example before people. We would like many more groups/societies to try and follow this experiment. Our interest is to have multitudes of such small social enterprises touching and bettering many rural livelihoods. This will become a nationwide movement when thousands of such enterprises will be established across India. What different message did Gandhiji give from his Charkha?

.

.