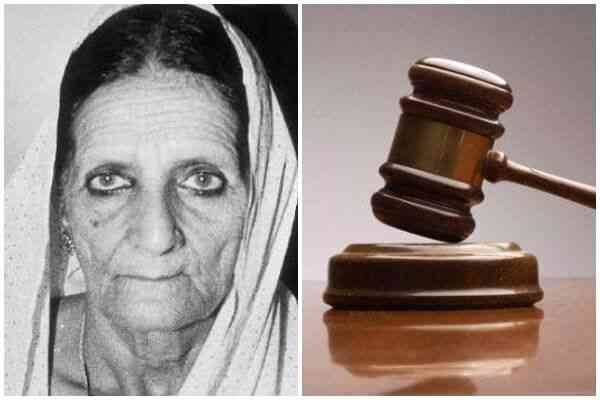

Shah Bano - Muslim Appeasement and Uniform Civil Code

Shah Bano appealed the amount of the award and eventually the High Court of Madhya Pradesh raised it to a hundred and seventy nine rupees and twenty paisa. On behalf of her husband lawyer Mohammad Ahmad refused to pay and appealed the decision to Supreme Court of India.

Total Views |

Early in 1978, in Indore, an indigent, illiterate Muslim woman, Shah Bano Begum filed a claim before the local Magistrate against her husband, Mohammad Ahmad Khan. She said, he had thrown her from their house. Her application demanded that her husband provide her with living-maintenances allowances, as Indian law required. She was about sixty-two years old and had been married to Mohammad Ahmad for about forty years and had borne him five children. Then, in November, her husband announced that he is divorcing her. In August 1979 the Court decided in favour of Shah Bano and ordered Mohammad Ahmad to pay her monthly livingmaintenances allowance of twenty five rupees.1

Shah Bano appealed the amount of the award and eventually the High Court of Madhya Pradesh raised it to a hundred and seventy nine rupees and twenty paisa. On behalf of her husband lawyer Mohammad Ahmad refused to pay and appealed the decision to Supreme Court of India. In April 1985 the Supreme Court also ruled in favour of Shah Bano holding that divorced Muslim woman, like other Indian women, were entitled to maintenance.

The bench of five Judges - Y.V. Chandrachud, Rangnath Misra, D.A. Desai, O. Chinnappa Reddy and E.S. Venkataramiah based their opinion primary of the Cr.PC of 1898 – more specifically on the Code as it had been revised in 1973. Judges had buttressed their argument with the reference of the Quran, to Islamic canonical and host of Islamic scholars.2

The honourable bench of Supreme Court also advised the Central Government to bring a Common law for every citizen of India, “Article 44 of our Constitution has remained a dead letter. There is no evidence of any official activity for framing a Common Civil Code for the country. A common Civil Code will help the cause of national integration by removing disparate loyalties to laws which have conflicting ideologies. It is the State which in charged with the duty of securing a uniform civil code for the citizens of the country and, unquestionably, it has the legislative competence to do so. A beginning has to be made if the Constitution is to have any meaning.” But the Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi himself rejected this observation of the Supreme Court of India.

Suddenly Muslim clerics, leaders of Muslim organisation, and fundamentalist Muslim politicians attacked the decision of Supreme Court as meddling in Muslim personal law and accused the Judges of setting themselves up as interpreters of Islam. Meanwhile, a General Secretary of Muslim League, G.M. Banatwalla introduced a Private Bill against the Supreme Court’s judgment on the Shah Bano case on 15 March, 1985. However, it was due to come up for the discussion in the Parliament.

After the decision of the Supreme Court, the said Bill became a matter of discussion. In August 1985, Minister of State in Ministry of Home Affairs Arif Mohammad Khan met the Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. Arif mentioned that he would like to speak on Banatwalla’s Bill. But the Prime Minister refused his request and said, “No, you might as well stay out of it. After all, you will just be saying what others are saying”.3

“That is just the point. I do not want to say what other are saying I am convinced that asking a husband to help look after an indigent woman whom he has divorced is in accord with the spirit of the Shariyat”, Arif told him. Then, Prime Minister Rajiv approved the idea of Arif speaking on the Bill. Benatwalla’s Bill had been addressed to the Ministry of Home Affairs. He was then the Minister of State in this Ministry. It was decided that he will speak on behalf of the Government.

The Home and Law Ministries had already prepared notes on the subject. Both had pointed out that personal law did not come into the question at all Section 125 of Cr.P.C., they said, was just meant to control vagrancy. The State had the right as well as the duty under the Constitution to control vagrancy. The religious argument, which was the premise of Banatwalla’s Bill, should therefore be rejected at the In his speech on 23 August, Arif established took a position on the basis of numerous Quranic texts, the Sunna of the Prophet in terms of Sharia itself.

Quran said: Oh Prophet Say to the wives if it be that ye seek the life of world and its adornment, then come, I shall make provision for you and shall release you a handsome release. [Translation: It is said here that being the wives of the Prophet, special duties devolved on them but if they wanted to escape from their innumerable duties and lead a life of ordinary women, he was prepared to release them and he would release them with a handsome release and would make such provision for them that they could lead comfortable life]. “I look upon the Shariayat with great respect. I think the Cr.P.C. can be changed and by changing those Mohammadans women can be deprived of their right who do not have any means of livelihood and who cannot go to the Courts but nobody can change the holy Quran. The Quran bestows this right on the women that they may lead a life of honour. Even Banatwalla Sahib cannot change the Quran.”5

He also cleared the Government position on the Uniform Civil Code, “I understand that Shri Banatwalla’s Bill is based on the judgment of the Supreme Court about which Banatwalla Shahib and a number of other honourable Members feel that it is an assault on the Muslim Personal Law or an interference with it. So far as a uniform civil code is concerned, the Government have made their stand clear not once but repeatedly and I do not think any further clarification is needed in that respect. After the Supreme Court judgement, the Prime Minister had made a statement…… However, the Supreme Court went a step further and gave its opinion about a uniform civil code also. But, since the Supreme Court has no power to frame a uniform civil code, it simply gave its opinion, after the judgement of the Supreme Court, when the Prime Minister made a statement clarifying the position on behalf of Government, I think that meant that we had rejected that opinion.”6

Finally, he was loudly cheered by Congress especially by the Prime Minister of India. The hero of the session, Arif became an asset for the Congress. Soon, things began to sour, as the election of 1985 in Assam got under ways. It was said within the Congress that Arif has alienated the Muslims; we must do something to win them back. Thus, the Central Government decided to change in the law that would take Muslim out of the purview of Section 125.

Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi had decided to disassociate himself from Arif’s stand on the Shah Bano case. In February Arif met Law Minister A.K. Sen. Sen told him that the Government had come to an understanding with the religious leaders. These leaders, Arif was astonished to learn, had now been accepted by the Government as spokesmen of the Muslim community. They included leaders of Muslim League, Muslim Majlis, Muslim Personal Law Board, Majlis Ijtihad-ulMusalmeen – each of them a rank of communal organisation. Arif pointed to the gross injustice of the Bill, how the law would now relegate Muslim women to a position abjectly inferior to that of other women in the country.7

Sen finally introduced the Bill on February 1986. A four times Lok Sabha Member from CPI (M) Saifuddin Chowdhary opposed the Bill, “This is a Black Bill. The heading of the Bill was also misleading. It was said that the Bill is to protect the rights of Muslim women. Actually, the Bill is meant for deprivation of their rights. This Bill violated the Preamble of the Constitution wherein it was resolved that State shall strive to constitute India into a secular country.”8

Even, the twelve times Lok Sabha Member from CPI Indrajit Gupta also opposed this Bill and gave his support in favour of Uniform Civil Code, “We may not always be able immediately to have a Common Civil Code. There are difficulties. I understand that. But the Constitution says that should be the direction in which the State should move; not the opposite direction. It may take a long time to reach the Common Code. There may be many difficulties and obstacles. But this Bill asks you to reverse, turn round, and not move towards a Uniform Civil Code, but to go backwards.”9

During the course of the discussion, the Law Minister himself exposed the Rajiv Gandhi Government’s plans of Muslim appeasement. He said, “It is true that the consultation with the Muslim leaders had a priority and was given more importance. And it must be so. When we are legislating on the personal law of a community, it is our bounden duty to give priority and importance to the views of that community. It is the declared policy of the Government since the time of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru that in matters of personal law the views of the community concerned must prevail and the Government will not move until a consensus had been reached in the community.10 The Congress Government under the leadership of Rajiv Gandhi had a good opportunity to write history, but he decided to go with the declared policy of communal appeasement that his grandfather had taught him. Whereas at that time the communists were also raising their voice for the Uniform Civil Code.

References:

1. Ved Mehta, Rajiv Gandhi and Rama’s Kingdom, Yale University: London, 1994, pp. 93-94

2. Ibid., p. 94

3. Arun Shourie, Religion in Politics, Roli Books: New Delhi, 1990, p. 91 threshold.4

4. Ibid., pp. 92-93

5. Lok Sabha Debates, Code of Cr.P.C. (Amendment) Bill, 23 August, 1985

6. Ibid.

7. 7 Arun Shourie, Religion in Politics, Roli Books: New Delhi, 1990, p. 94

8. Lok Sabha Debates, Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce Bill), 25 February, 1986

9. Ibid.

.

.