What Does the Exit of 6,688 Companies Tell Us About Governance in West Bengal?

Total Views |

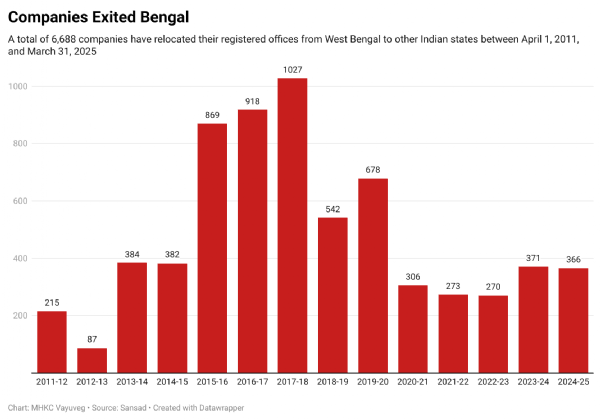

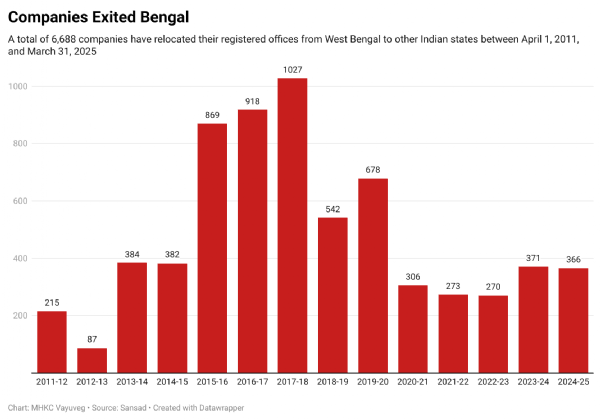

Once known for its industries and enterprise, West Bengal faces an unsettling trend: businesses are being relocated out of the state. No sensational headlines, no protests. Just the fact that 6,688 companies have shifted their registered offices out of Bengal over the past decade. The exodus, which has been accelerating since the TMC came to power in 2011, is not random. Moreover, the Mamata Banerjee government was left red-faced when these firms chose BJP-ruled states such as Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, etc, where policy is predictable and the political climate more welcoming.

For the average citizen, these numbers may seem surprising. But a closer look reveals that the Mamata Banerjee government has long been associated with the steady outflow of industries from West Bengal. On average, around 477 companies left the state each year. Now this is an unmistakable sign of the gradual erosion of Bengal’s industrial foundation.

The trend, however, was not uniform. Between 2015–16 and 2017–18, there was a sharp rise in company relocations. In these three years, 2,814 firms moved out, accounting for more than 42% of the total departures. The exodus peaked in 2017–18, when 1,027 companies shifted their registered offices elsewhere. This marked a clear turning point in business sentiment.

This period is particularly telling. The years from 2011 to 2015 appear to have been a “wait and watch” phase, during which businesses assessed the policies of the new TMC government. The spike in relocations after 2015 suggests that many concluded the state’s business environment was not improving, and likely would not.

What is even more concerning is the profile of the companies that left. Among them were 110 firms listed on the stock exchange — large, established entities with substantial investments, employment, and public responsibility. Their exit sends a clear and troubling signal to the broader investment community: that West Bengal is increasingly seen as a risky and unattractive place to do business. So, where are these companies going and why?

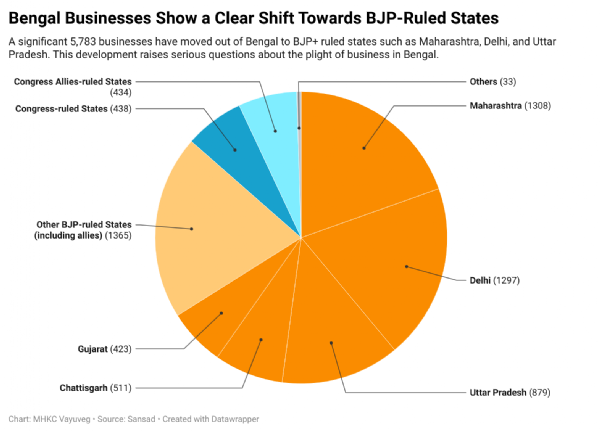

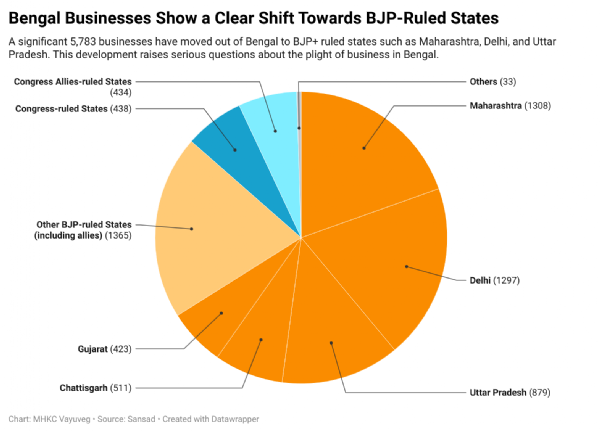

The data given by the central government also reveals a strong magnetic pull towards states with reputations for being more business-friendly and having more stable policy regimes. These states are mainly ruled by the BJP. Maharashtra and Delhi emerged as the top destinations, attracting 1,308 and 1,297 companies respectively. Uttar Pradesh followed by drawing 879 companies. Together, these three destinations accounted for 3,484 relocations which represents a commanding 52% of the total exodus. Other states like Chhattisgarh (511), Gujarat (423), Rajasthan and Assam.

The states where these companies have relocated offer clear, incentive-driven policies that actively promote industrial growth. In contrast, TMC and Congress-ruled states have been marked by policy uncertainty and weak support for businesses. This migration underscores the logic of competitive federalism, where capital flows toward regions that provide stability and long-term growth and away from those seen as unpredictable and investor-unfriendly. Despite high-profile summits and announcements, the ground reality tells a different story

The mass relocation of companies from West Bengal is not a random event, but it reflects deeper problems in the state's economy. It shows a weak industrial base, a lack of trust from investors and repeated failure to convert potential into real progress. One of the TMC government’s most publicised events is the Bengal Global Business Summit, which routinely announces massive investment proposals. However, despite the headlines, actual capital inflow tells a very different story.

A glaring example is found in the DPIIT Annual Report 2024–25: West Bengal ranked 4th in investment intentions between January and November 2024, with proposals worth ₹39,133 crore, accounting for 7.45% of total IEM Part A filings. Yet, in terms of actual investment realised (IEM Part B), Bengal fell to 14th place, receiving only ₹3,735 crore. It is a mere 1.2% of total national investment, and down from ₹4,930 crore in 2023. This stark mismatch between intent and realisation exposes a fundamental lack of investor confidence. It suggests that businesses are willing to express interest on paper but hesitate to commit real capital.

Speaking of its GSDP, West Bengal’s share of the national GDP has also witnessed a sharp fall, from 10.5% in 1960–61 when it held the third-largest share, to just 5.6% in 2023–24. Apart from this, a major red flag is Bengal’s absence from the India Industrial Land Bank, a GIS-enabled national platform launched in August 2020, which now includes data from 2,884 industrial parks across 35 States and UTs. West Bengal remains the only major state not onboard, highlighting its reluctance to adopt basic tools that support industrial planning and land transparency. These are the key components that fit within the Ease of Doing Business framework.

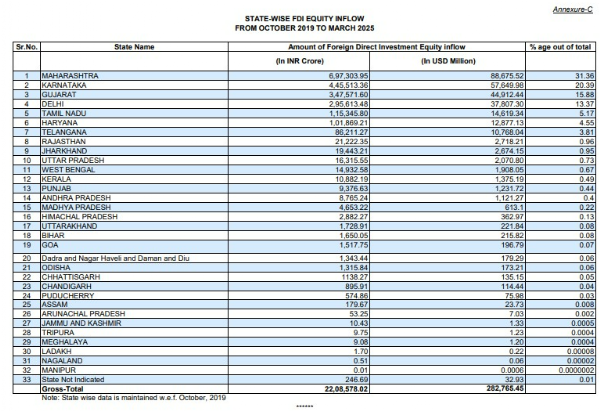

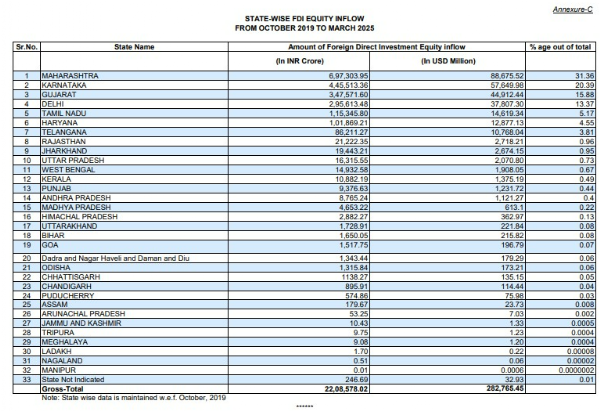

This trend is also mirrored in the state's performance in attracting Foreign Direct Investment. Despite being India's fourth-most populous state, West Bengal ranks a poor 11th in cumulative FDI inflows.

The Singur legacy and land acquisition paralysis: West Bengal’s industrial decline began with the 2008 Singur agitation, where Mamata Banerjee led protests against land acquisition for Tata’s Nano plant. After coming to power, her government adopted a “hands-off” policy, refusing to help acquire land for industries. This forced private companies to deal with thousands of small landowners directly, making large projects nearly impossible.

Policies benefitting industries abolished: In April 2025, the Mamata Banerjee government stopped all eight state-run industrial schemes that were launched since 1993. This sudden move stunned investors and severely impacted companies such as Dalmia Bharat and Birla Corporation, which collectively lost nearly ₹430 crore in pending claims.

Industries moving out of Bengal are not just an issue for the state but also for the nation. As the country’s fourth-most populous state, Bengal’s economic underperformance slows India’s overall growth and worsens regional inequality. The exit of 6,688 companies means thousands of formal sector jobs lost. With fewer opportunities, many skilled professionals are forced to leave the state.

Moreover, West Bengal's 14-year trajectory under Mamata Banerjee also offers a clear lesson: in today’s economy, good governance matters. Without stable policies, legal certainty, and government support, no amount of political rhetoric can attract investment. The state has fallen into a dependency trap, relying on central transfers to fund welfare schemes while avoiding real reforms. This weakens not just Bengal, but the broader goal of building a strong, self-reliant India.

Though the companies relocated to other states, they delivered a clear signal on a governance model that failed to deliver economic security or industrial growth.

For the average citizen, these numbers may seem surprising. But a closer look reveals that the Mamata Banerjee government has long been associated with the steady outflow of industries from West Bengal. On average, around 477 companies left the state each year. Now this is an unmistakable sign of the gradual erosion of Bengal’s industrial foundation.

The trend, however, was not uniform. Between 2015–16 and 2017–18, there was a sharp rise in company relocations. In these three years, 2,814 firms moved out, accounting for more than 42% of the total departures. The exodus peaked in 2017–18, when 1,027 companies shifted their registered offices elsewhere. This marked a clear turning point in business sentiment.

This period is particularly telling. The years from 2011 to 2015 appear to have been a “wait and watch” phase, during which businesses assessed the policies of the new TMC government. The spike in relocations after 2015 suggests that many concluded the state’s business environment was not improving, and likely would not.

What is even more concerning is the profile of the companies that left. Among them were 110 firms listed on the stock exchange — large, established entities with substantial investments, employment, and public responsibility. Their exit sends a clear and troubling signal to the broader investment community: that West Bengal is increasingly seen as a risky and unattractive place to do business. So, where are these companies going and why?

BJP-ruled states become preferred destinations

The data given by the central government also reveals a strong magnetic pull towards states with reputations for being more business-friendly and having more stable policy regimes. These states are mainly ruled by the BJP. Maharashtra and Delhi emerged as the top destinations, attracting 1,308 and 1,297 companies respectively. Uttar Pradesh followed by drawing 879 companies. Together, these three destinations accounted for 3,484 relocations which represents a commanding 52% of the total exodus. Other states like Chhattisgarh (511), Gujarat (423), Rajasthan and Assam.

The states where these companies have relocated offer clear, incentive-driven policies that actively promote industrial growth. In contrast, TMC and Congress-ruled states have been marked by policy uncertainty and weak support for businesses. This migration underscores the logic of competitive federalism, where capital flows toward regions that provide stability and long-term growth and away from those seen as unpredictable and investor-unfriendly. Despite high-profile summits and announcements, the ground reality tells a different story

A gap between promises and delivery

The mass relocation of companies from West Bengal is not a random event, but it reflects deeper problems in the state's economy. It shows a weak industrial base, a lack of trust from investors and repeated failure to convert potential into real progress. One of the TMC government’s most publicised events is the Bengal Global Business Summit, which routinely announces massive investment proposals. However, despite the headlines, actual capital inflow tells a very different story.

A glaring example is found in the DPIIT Annual Report 2024–25: West Bengal ranked 4th in investment intentions between January and November 2024, with proposals worth ₹39,133 crore, accounting for 7.45% of total IEM Part A filings. Yet, in terms of actual investment realised (IEM Part B), Bengal fell to 14th place, receiving only ₹3,735 crore. It is a mere 1.2% of total national investment, and down from ₹4,930 crore in 2023. This stark mismatch between intent and realisation exposes a fundamental lack of investor confidence. It suggests that businesses are willing to express interest on paper but hesitate to commit real capital.

Speaking of its GSDP, West Bengal’s share of the national GDP has also witnessed a sharp fall, from 10.5% in 1960–61 when it held the third-largest share, to just 5.6% in 2023–24. Apart from this, a major red flag is Bengal’s absence from the India Industrial Land Bank, a GIS-enabled national platform launched in August 2020, which now includes data from 2,884 industrial parks across 35 States and UTs. West Bengal remains the only major state not onboard, highlighting its reluctance to adopt basic tools that support industrial planning and land transparency. These are the key components that fit within the Ease of Doing Business framework.

This trend is also mirrored in the state's performance in attracting Foreign Direct Investment. Despite being India's fourth-most populous state, West Bengal ranks a poor 11th in cumulative FDI inflows.

Policy and governance: the root causes

The Singur legacy and land acquisition paralysis: West Bengal’s industrial decline began with the 2008 Singur agitation, where Mamata Banerjee led protests against land acquisition for Tata’s Nano plant. After coming to power, her government adopted a “hands-off” policy, refusing to help acquire land for industries. This forced private companies to deal with thousands of small landowners directly, making large projects nearly impossible.

Policies benefitting industries abolished: In April 2025, the Mamata Banerjee government stopped all eight state-run industrial schemes that were launched since 1993. This sudden move stunned investors and severely impacted companies such as Dalmia Bharat and Birla Corporation, which collectively lost nearly ₹430 crore in pending claims.

Broader implications of Bengal’s decline

Industries moving out of Bengal are not just an issue for the state but also for the nation. As the country’s fourth-most populous state, Bengal’s economic underperformance slows India’s overall growth and worsens regional inequality. The exit of 6,688 companies means thousands of formal sector jobs lost. With fewer opportunities, many skilled professionals are forced to leave the state.

Moreover, West Bengal's 14-year trajectory under Mamata Banerjee also offers a clear lesson: in today’s economy, good governance matters. Without stable policies, legal certainty, and government support, no amount of political rhetoric can attract investment. The state has fallen into a dependency trap, relying on central transfers to fund welfare schemes while avoiding real reforms. This weakens not just Bengal, but the broader goal of building a strong, self-reliant India.

Though the companies relocated to other states, they delivered a clear signal on a governance model that failed to deliver economic security or industrial growth.