Who is Michael Thevar? Christian Convert, Caste Campaigner, and the Man Behind ‘Khalid ka Shivaji’?

Total Views |

Michael Muthaiah Thevar, the 58-year-old producer of the controversial Marathi film Khalid ka Shivaji, seems not to be entering cinema for the sake of producing movies but for a larger propaganda. The film is part of a larger project to distort Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s legacy through diluting his Hindutva-rooted mission into a secularist narrative that aligns with Thevar’s long-standing worldview.

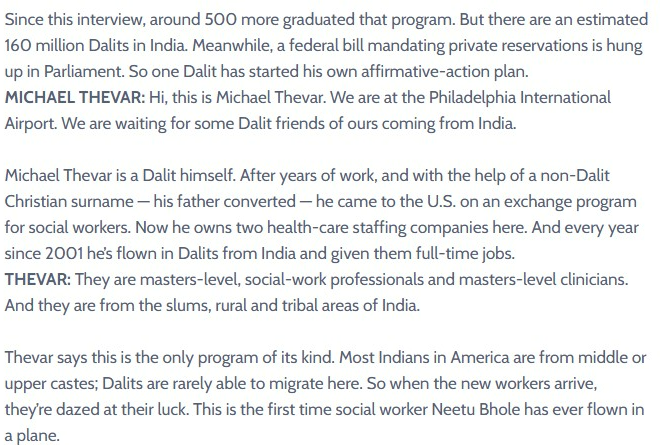

Hailing from Dandeli, Karnataka, Thevar comes from a Dalit background — his father’s conversion to Christianity offered the family a path to global liberal spaces under a non-Dalit Christian surname. A native Tamil speaker, Thevar studied at St. Michael’s Convent School, completed his bachelor’s degree from Nirmala Niketan College, Mumbai, and earned a Master of Social Work from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. During his MSW, he engaged with tribal communities in Thane district, laying the groundwork for his future activism.

Erects a Whole Empire in America?

In the early 2000s, Thevar moved to the United States, where he built an expansive healthcare business empire. In 2000, he co-founded Temp Solutions Inc., a healthcare staffing agency, with his wife, Sushma Thevar (born Sushma Ganvir, also Dalit). In 2007, they launched Omni Health Services Inc. in Pennsylvania, growing it from a single clinic to a 17-branch behavioural healthcare chain across Pennsylvania and New Jersey. This was followed by the Indian arm, Omni Health Services Pvt. Ltd., in Mumbai, focusing on mental health for underprivileged populations with training links to U.S. professionals.

Alongside his corporate ventures, Thevar co-founded the Organisation for Dalit Rights and Freedom (ODRF) in 2007. A human rights NGO, ODRF, is deeply rooted in Ambedkarite-Periyarist ideology. Its public events consistently glorify Periyar, Mahatma Phule, Narayana Guru, and Kanshi Ram, while conspicuously omitting icons of Hindu resistance such as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, except when his legacy can be distorted to fit a secular script.

At ODRF’s first anniversary, Thevar’s speech was drenched in ideological signalling, praising his preferred icons but entirely ignoring Shivaji Maharaj. Across years of interviews, articles, and public appearances, Shivaji’s name remained absent. The sudden appearance of Khalid ka Shivaji under his banner thus signals not homage, but appropriation — an attempt to fit Shivaji as a “secular” ruler whose Hindavi Swarajya is downplayed in favour of a syncretic, politically useful image.

Historians acknowledge that Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj respected all faiths, but his aim to establish Swarajya was fundamentally tied to the defence of Hindu Dharma and culture. Thevar’s film — and the ideological current it represents — seeks to obscure this fact. Such narratives do not arise in isolation; they align with a wider coalition of left-leaning historians, Islamist voices, and self-styled “progressives” who selectively distort history to suit their agendas.

Thevar’s ideological export is not confined to film. Through ODRF, he has actively participated in international lobbying, drawing parallels between caste in India and racial discrimination in the West. His article Being Black in India exemplifies this approach — narrating personal experiences of colour bias and generalising them to portray Indian society as inherently casteist, racist, and obsessed with fair skin. While prejudice exists, Thevar’s framing presents India in an unrelentingly negative light on global platforms, softening criticism only with token declarations of love for the country.

Khalid ka Shivaji thus stands not as an isolated creative venture, but as a deliberate act of cultural re-engineering — one that demands scrutiny from historians, cultural custodians, and an aware public. In the battle for India’s historical memory, such portrayals are not just stories on screen; they are weapons in an ongoing war of narratives.

Family Background

Hailing from Dandeli, Karnataka, Thevar comes from a Dalit background — his father’s conversion to Christianity offered the family a path to global liberal spaces under a non-Dalit Christian surname. A native Tamil speaker, Thevar studied at St. Michael’s Convent School, completed his bachelor’s degree from Nirmala Niketan College, Mumbai, and earned a Master of Social Work from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. During his MSW, he engaged with tribal communities in Thane district, laying the groundwork for his future activism.

Erects a Whole Empire in America?

In the early 2000s, Thevar moved to the United States, where he built an expansive healthcare business empire. In 2000, he co-founded Temp Solutions Inc., a healthcare staffing agency, with his wife, Sushma Thevar (born Sushma Ganvir, also Dalit). In 2007, they launched Omni Health Services Inc. in Pennsylvania, growing it from a single clinic to a 17-branch behavioural healthcare chain across Pennsylvania and New Jersey. This was followed by the Indian arm, Omni Health Services Pvt. Ltd., in Mumbai, focusing on mental health for underprivileged populations with training links to U.S. professionals.

Organisation for Dalit Rights and Freedom

Alongside his corporate ventures, Thevar co-founded the Organisation for Dalit Rights and Freedom (ODRF) in 2007. A human rights NGO, ODRF, is deeply rooted in Ambedkarite-Periyarist ideology. Its public events consistently glorify Periyar, Mahatma Phule, Narayana Guru, and Kanshi Ram, while conspicuously omitting icons of Hindu resistance such as Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, except when his legacy can be distorted to fit a secular script.

At ODRF’s first anniversary, Thevar’s speech was drenched in ideological signalling, praising his preferred icons but entirely ignoring Shivaji Maharaj. Across years of interviews, articles, and public appearances, Shivaji’s name remained absent. The sudden appearance of Khalid ka Shivaji under his banner thus signals not homage, but appropriation — an attempt to fit Shivaji as a “secular” ruler whose Hindavi Swarajya is downplayed in favour of a syncretic, politically useful image.

Historians acknowledge that Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj respected all faiths, but his aim to establish Swarajya was fundamentally tied to the defence of Hindu Dharma and culture. Thevar’s film — and the ideological current it represents — seeks to obscure this fact. Such narratives do not arise in isolation; they align with a wider coalition of left-leaning historians, Islamist voices, and self-styled “progressives” who selectively distort history to suit their agendas.

Thevar’s ideological export is not confined to film. Through ODRF, he has actively participated in international lobbying, drawing parallels between caste in India and racial discrimination in the West. His article Being Black in India exemplifies this approach — narrating personal experiences of colour bias and generalising them to portray Indian society as inherently casteist, racist, and obsessed with fair skin. While prejudice exists, Thevar’s framing presents India in an unrelentingly negative light on global platforms, softening criticism only with token declarations of love for the country.

Khalid ka Shivaji thus stands not as an isolated creative venture, but as a deliberate act of cultural re-engineering — one that demands scrutiny from historians, cultural custodians, and an aware public. In the battle for India’s historical memory, such portrayals are not just stories on screen; they are weapons in an ongoing war of narratives.