How West Bengal’s Demography is Changing

Total Views |

In the fertile plains where the Ganges meets the Bay of Bengal, West Bengal has witnessed a quiet yet profound demographic transformation since Partition. What began in 1947 as a reshaping of borders has today become a reshaping of identities. Over the decades, a steady inflow of migrants from Bangladesh has altered not just population figures, but also the cultural, social, and political fabric of the state.

Numbers That Tell the Story

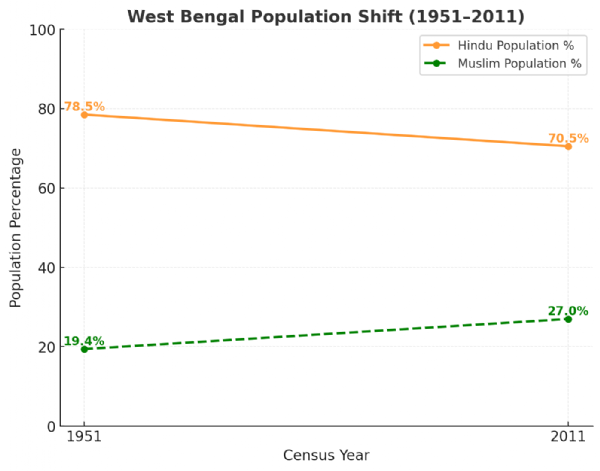

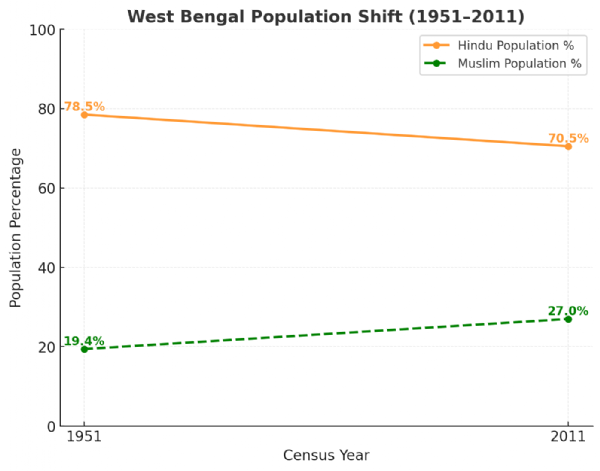

Census data reveals the trajectory clearly. In 1951, Hindus accounted for 78.45% of West Bengal’s population, while Muslims were 19.85%. By 2011, Hindus dropped to 70.54% and Muslims rose to 27.01%—over 24.6 million Muslims in a state of 91 million. Projections for 2025 suggest Muslims may reach 30–35%, driven by higher fertility rates and ongoing infiltration.

The impact is most visible in border districts:

Murshidabad: 66.27% Muslim

Malda: 51.27% Muslim

North 24 Parganas: 26% overall, with pockets above 60%

These demographic realities form the backdrop to recurring violence, such as the April 2025 Murshidabad riots over Waqf Act amendments, which Ministry of Home Affairs probes linked to Bangladeshi infiltrators.

From Partition to Present: The Infiltration Pipeline

The 4,096-km Indo-Bangladesh border, with its riverine stretches and long unfenced sections, has long been porous. Partition opened the first breaches as Hindus fled westward and Muslims crossed in the opposite direction. By the 1950s and 1960s, migration intensified, spurred by East Pakistan’s communal tensions and economic hardship. The 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War displaced millions more.

While Hindu refugees sought asylum through official channels, Muslim migrants often blended seamlessly into existing Muslim-majority villages. Organized networks soon professionalized the crossings, charging Rs 7,000–10,000 for poor farmers and up to lakhs for those fleeing prosecution.

By the 1980s, infiltration had become a structured racket. Intelligence Bureau officials described it as “a well-oiled machinery” involving traffickers, corrupt officials, and local political patrons.

Case Studies: Proof of Entrenchment

Abdul Majed, convicted in Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s assassination, lived undetected in Kolkata for 23 years, holding an Indian passport and local identity papers, until his arrest in 2020.

Risaldar Moslehuddin, another Mujib assassin, resided in Bongaon for over two decades, equipped with voter ID and Aadhaar, while running a small medicine trade.

Palash Adhikari, arrested in Madhya Pradesh in 2023, turned out to be Sheikh Moinuddin from Khulna, Bangladesh—his forged documents facilitated by local political figures.

Such cases highlight the scale of infiltration and the ease with which outsiders gain legitimacy.

Settlers to Enforcers: Economic and Social Impact

Once inside Bengal, migrants moved quickly from survival to dominance in key economic sectors. In border districts, they came to control fisheries (bheris), street vending, and small-scale trades. Local Hindus, displaced from traditional livelihoods, often migrated elsewhere.

The case of Sandeshkhali in North 24 Parganas illustrates the trajectory. Rohingyas arrived as fishery workers nearly a decade ago but soon became enforcers for local TMC strongman Sheikh Shahjahan. Locals testify that shelters, jobs, and protection were provided directly by ruling party leaders.

Cultural erosion followed economic displacement. In Kaliganj, Muslims rose from 45.3% in 1971 to over 61% by 2025, leading to objections against Hindu rituals and altered festival practices. Villagers like Shaktipada Das, a Namasudra refugee, recount selling land and moving inland after harassment during the 1980s—only to face similar pressures again.

Radical influences have deepened the divide. Retired police officer Soumitra Pramanik observed increasing burqa adoption, madrassa-based indoctrination, and a rise in assertive behaviour among youth. He attributed this to political appeasement: “Police cannot touch them; the system protects them.”

The Fake Identity Industry

The backbone of infiltration has been forged identity. In border towns, fake Aadhaar cards fetch Rs 20,000, while passports cost Rs 40,000. Families secure “package deals” to establish entire households as citizens.

Enforcement Directorate raids in 2019 exposed networks generating Rs 5,000 crore annually—Rs 3,000 crore from forged documents and Rs 1,000 crore from trafficking fees. Officials estimate at least 100,000 new infiltrators annually.

Political complicity is evident. Panchayats in Sandeshkhali facilitated Rohingyas in acquiring IDs, cementing their role as TMC enforcers. BJP leaders accuse the ruling party of nurturing this ecosystem for electoral advantage, while Mamata Banerjee dismisses crackdowns in other states as “anti-Bengali.”

Beyond Bengal: A Spreading Pattern

The ripple effects of infiltration extend beyond state borders. In Sambalpur, Odisha, Bangladeshi-origin Muslims who arrived as laborers two decades ago now comprise 9% of the population, building mosques and triggering tensions, including violence during the 2023 Rath Yatra.

The unfolding reality in Bengal is not merely a matter of migration. It is a question of sovereignty, cultural continuity, and national security. Decades of porous borders, organized infiltration, and political appeasement have entrenched a demographic imbalance now altering the state’s very identity.

As projections indicate Muslims nearing 35% of the population by 2030, the urgency for stronger borders, document audits, and political accountability grows sharper. In the words of one retired BSF officer: “This isn’t just about religion. It’s about sovereignty, resources, and the soul of Bengal.”

Numbers That Tell the Story

Census data reveals the trajectory clearly. In 1951, Hindus accounted for 78.45% of West Bengal’s population, while Muslims were 19.85%. By 2011, Hindus dropped to 70.54% and Muslims rose to 27.01%—over 24.6 million Muslims in a state of 91 million. Projections for 2025 suggest Muslims may reach 30–35%, driven by higher fertility rates and ongoing infiltration.

The impact is most visible in border districts:

Murshidabad: 66.27% Muslim

Malda: 51.27% Muslim

North 24 Parganas: 26% overall, with pockets above 60%

These demographic realities form the backdrop to recurring violence, such as the April 2025 Murshidabad riots over Waqf Act amendments, which Ministry of Home Affairs probes linked to Bangladeshi infiltrators.

From Partition to Present: The Infiltration Pipeline

The 4,096-km Indo-Bangladesh border, with its riverine stretches and long unfenced sections, has long been porous. Partition opened the first breaches as Hindus fled westward and Muslims crossed in the opposite direction. By the 1950s and 1960s, migration intensified, spurred by East Pakistan’s communal tensions and economic hardship. The 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War displaced millions more.

While Hindu refugees sought asylum through official channels, Muslim migrants often blended seamlessly into existing Muslim-majority villages. Organized networks soon professionalized the crossings, charging Rs 7,000–10,000 for poor farmers and up to lakhs for those fleeing prosecution.

By the 1980s, infiltration had become a structured racket. Intelligence Bureau officials described it as “a well-oiled machinery” involving traffickers, corrupt officials, and local political patrons.

Case Studies: Proof of Entrenchment

Abdul Majed, convicted in Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s assassination, lived undetected in Kolkata for 23 years, holding an Indian passport and local identity papers, until his arrest in 2020.

Risaldar Moslehuddin, another Mujib assassin, resided in Bongaon for over two decades, equipped with voter ID and Aadhaar, while running a small medicine trade.

Palash Adhikari, arrested in Madhya Pradesh in 2023, turned out to be Sheikh Moinuddin from Khulna, Bangladesh—his forged documents facilitated by local political figures.

Such cases highlight the scale of infiltration and the ease with which outsiders gain legitimacy.

Settlers to Enforcers: Economic and Social Impact

Once inside Bengal, migrants moved quickly from survival to dominance in key economic sectors. In border districts, they came to control fisheries (bheris), street vending, and small-scale trades. Local Hindus, displaced from traditional livelihoods, often migrated elsewhere.

The case of Sandeshkhali in North 24 Parganas illustrates the trajectory. Rohingyas arrived as fishery workers nearly a decade ago but soon became enforcers for local TMC strongman Sheikh Shahjahan. Locals testify that shelters, jobs, and protection were provided directly by ruling party leaders.

Cultural erosion followed economic displacement. In Kaliganj, Muslims rose from 45.3% in 1971 to over 61% by 2025, leading to objections against Hindu rituals and altered festival practices. Villagers like Shaktipada Das, a Namasudra refugee, recount selling land and moving inland after harassment during the 1980s—only to face similar pressures again.

Radical influences have deepened the divide. Retired police officer Soumitra Pramanik observed increasing burqa adoption, madrassa-based indoctrination, and a rise in assertive behaviour among youth. He attributed this to political appeasement: “Police cannot touch them; the system protects them.”

The Fake Identity Industry

The backbone of infiltration has been forged identity. In border towns, fake Aadhaar cards fetch Rs 20,000, while passports cost Rs 40,000. Families secure “package deals” to establish entire households as citizens.

Enforcement Directorate raids in 2019 exposed networks generating Rs 5,000 crore annually—Rs 3,000 crore from forged documents and Rs 1,000 crore from trafficking fees. Officials estimate at least 100,000 new infiltrators annually.

Political complicity is evident. Panchayats in Sandeshkhali facilitated Rohingyas in acquiring IDs, cementing their role as TMC enforcers. BJP leaders accuse the ruling party of nurturing this ecosystem for electoral advantage, while Mamata Banerjee dismisses crackdowns in other states as “anti-Bengali.”

Beyond Bengal: A Spreading Pattern

The ripple effects of infiltration extend beyond state borders. In Sambalpur, Odisha, Bangladeshi-origin Muslims who arrived as laborers two decades ago now comprise 9% of the population, building mosques and triggering tensions, including violence during the 2023 Rath Yatra.

The unfolding reality in Bengal is not merely a matter of migration. It is a question of sovereignty, cultural continuity, and national security. Decades of porous borders, organized infiltration, and political appeasement have entrenched a demographic imbalance now altering the state’s very identity.

As projections indicate Muslims nearing 35% of the population by 2030, the urgency for stronger borders, document audits, and political accountability grows sharper. In the words of one retired BSF officer: “This isn’t just about religion. It’s about sovereignty, resources, and the soul of Bengal.”