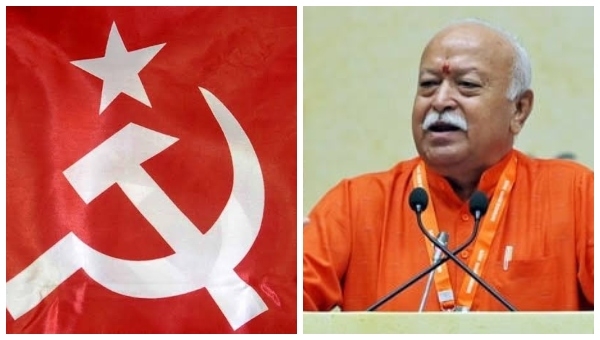

CPI(M) Stand on Mohan Bhagwat’s Speech: A Reflection of its Ideological Bankruptcy & Consistent Political Failure

30 Aug 2025 18:38:57

The recent statement of CPI(M) against RSS Sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat’s Delhi speech has once again exposed the ideological hollowness of a party that has long been a spent force in country’s politics. Instead of engaging with the aspirations of the majority population and the larger socio-political discourse of a resurgent Bharat, the CPI(M) has chosen its old path of rigid opposition to anything rooted in Bhartiya cultural nationalism. What was expected from a national political party was sober analysis, dialogue, and constructive suggestions. What it delivered instead was a predictable rejection of Hindu concerns, in line with its old record of standing against Bharat’s civilisational ethos.

A Party Reduced to Irrelevance

The Communist Party of India (Marxist) is today reduced to a marginal force, surviving merely as a shadow of its past glory. The statistics speak for themselves. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, CPI(M) could win only three seats out of 543, a humiliating decline from the 43 seats it held in 2004 when it still retained influence in West Bengal, Kerala, and Tripura. This downward spiral has continued in the states as well.

West Bengal, once the party’s impregnable bastion, witnessed CPI(M) ruling uninterruptedly for 34 long years. That dominance, however, collapsed suddenly in 2011 when the people decisively rejected the Left regime. The 2021 Assembly elections dealt an even greater blow—CPI(M) faced it’s complete collapse of its political base in the very state that had once carried the red flag for decades.

In Tripura too, which the CPI(M) ruled for over two decades, the party has been dethroned by the BJP. Its grassroots machinery has weakened, and its cadre-based politics has been overtaken by aspirational politics and nationalist narratives. Kerala remains its last standing fortress, where the Left Democratic Front (LDF) continues to hold power. Yet, even here, the party faces a narrowing margin amidst changing socio-political realities, scandals, and shifting youth preferences. LDF had to borrow support from outside to form the government.

Thus, the picture is crystal clear: CPI(M) today has neither electoral strength nor mass connect.

Doubts also persist about strength and influence of once motivated and committed party cadre. It survives largely through occasional media noise, ideological grandstanding, and ritualistic opposition to cultural-nationalist narratives, rather than any genuine mass appeal.

Ideological Decay and Global Context

The erosion of CPI(M)’s base is not only political but deeply ideological. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the retreat of communism in Eastern Europe, and the Chinese Communist Party’s shift towards market-driven economics have rendered classical Marxism outdated. Across the globe, communist parties have either reinvented themselves or faded into irrelevance.

In Bharat, CPI(M) continues to cling to obsolete slogans, outdated class-struggle theories, and borrowed ideological constructs. Its leadership has remained trapped in a time warp, refusing to accept that the world has moved on. While people across nations have chosen economic growth, cultural pride, and national unity, CPI(M) insists on recycling the same dogmas that no longer resonate with 21st-century realities.

It is telling that while the CPI(M) is celebrating its centenary this year, the event has gone largely unnoticed. The indifference of the Indian public reflects the irrelevance of a party that has failed to adapt, failed to reform, and failed to connect with the aspirations of a new Bharat.

The Places of Worship Act Debate

The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which froze the status of religious sites as of August 15, 1947, has been widely criticised. When it was enacted, several legal experts, scholars, and community leaders opposed it, arguing that it denied Hindus their legitimate right to reclaim sacred spaces, particularly Kashi and Mathura. For a civilisation that has endured centuries of invasions, desecrations, and temple destructions, the act came as a denial of justice.

CPI(M), however, has always stood against such demands. True to its history of neglecting Hindu sentiments, the party once again criticised Bhagwat’s remarks. The question arises—what harm would it do if Muslims voluntarily surrendered Kashi and Mathura as a goodwill gesture to resolve centuries-old disputes? Such an act could become a bridge of reconciliation, building lasting harmony. But CPI(M), instead of encouraging reconciliation, chooses to paint any assertion of Hindu sentiment as “majoritarianism.” This exposes not only its double standards but also its complete disconnect from the cultural ethos of the land.

Historical Neglect of Hindu Sentiments

CPI(M)’s stance is not new. From the very beginning, Communists have been accused of ignoring Hindu aspirations while siding with divisive forces. During the partition era, Communist leaders acted in collusion with the Muslim League, supporting religion-based partition under the pretext of “historical necessity.” This mindset of appeasement and disregard for Hindu concerns continues even today.

Whether it is temple issues, matters of national security, or expressions of faith, CPI(M) consistently positions itself against majority sentiment, thereby alienating itself further from the mainstream. The party’s record is full of such examples: its opposition to the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, its repeated criticism of Hindu organisations, and its silence on atrocities against Hindus in West Bengal and Kerala.

A telling example is that of CPI(M) leader Sitaram Yechury, who was invited for the consecration ceremony in Ayodhya. He not only declined the invitation but also ridiculed Hindu sentiments, thus reinforcing the perception that the party considers Hindu aspirations inferior, if not illegitimate.

Imported Ideology, No Indian Connect

The root cause of CPI(M)’s irrelevance lies in its imported ideology. Communism in India never evolved organically from Bhartiya soil; it was transplanted wholesale from Soviet and Chinese models. This foreign inspiration prevented the party from understanding the civilisational roots of Bhartiya society.

While organisations like the RSS have grown by staying connected to the ground—running shakhas, engaging in social service, addressing cultural issues, and cultivating grassroots workers—the CPI(M) has remained a prisoner of abstract dogma. Its cadres may still chant Marxist slogans, but those chants carry no echo in Bharat’s villages, temples, or families.

The CPI(M)’s reaction to Mohan Bhagwat’s Delhi speech is not surprising—it is merely a continuation of its decades-long practice of belittling Hindu sentiments and aligning itself with external ideological frameworks. With its electoral base decimated, its ideological relevance eroded, and its centenary celebrations barely noticed, CPI(M) today resembles a relic of the past rather than a force of the future.

Its criticism of Bhagwat is less about principles and more about survival—an attempt to remain visible in public discourse. But as Bharat marches forward, rooted in its civilisational ethos while embracing modernity, CPI(M)’s outdated politics will find fewer takers.

It is also symbolic to compare histories: the Communist Party was founded in Bharat in 1924, and its centenary has gone almost entirely unnoticed. By contrast, the RSS was founded in 1925, and its centenary is being celebrated with national and global participation. The divergent journeys of these two schools of thought are open for examination.

The crucial question remains—will my Comrades ever have the courage for robust self-introspection? Or will they continue along the same path of ideological rigidity, cultural alienation, and political irrelevance? If the past and present are any indicators, the CPI(M)’s future seems destined only for the footnotes of history.