Who Controls the Universe’s Story?

20 Sep 2025 09:28:26

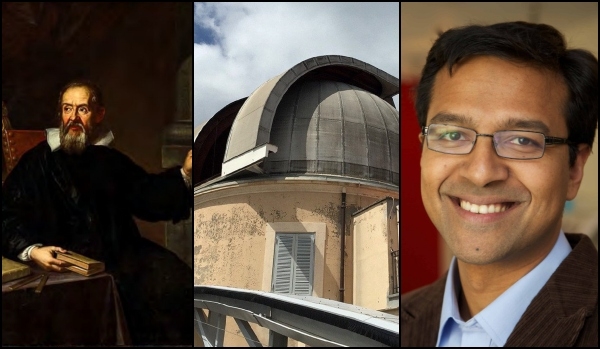

Father Richard D’Souza SJ, an astrophysicist of Indian origin, has been appointed as the new Director of the Vatican Observatory. For Catholic communities in India, this announcement has been a moment of celebration, held up as a symbol of harmony between faith and science. The pride is understandable: a son of Goa, educated in physics and astronomy, is now placed at the helm of one of the most visible scientific institutions of the Catholic Church.

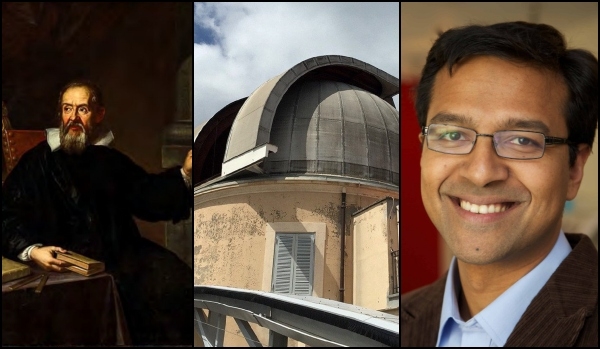

Yet behind the applause lie deeper questions. Can the same Church that condemned Galileo, censored Copernicus, and resisted scientific discoveries for centuries now be trusted as the guardian of science? Or does this appointment mark another moment in a long history of presenting theology under the mantle of astronomy, with clerical obedience still placed above free inquiry? What appears as progress may, in fact, be strategy—an old story retold in new language.

The Vatican Observatory has always existed in the tension between faith and evidence. Re-established in 1891 by Pope Leo XIII, it was not born of curiosity alone. Its stated purpose was to “counter accusations of hostility of the Church toward science.” The gesture was defensive, meant to improve the Church’s image at a time when modern science was rapidly distancing itself from dogma.

Since then, almost every director of the Observatory has come from the Jesuit order—Johann Hagen in the early years, later George Coyne, José Gabriel Funes, Guy Consolmagno, and now Father D’Souza. In other words, leadership has been reserved for priests rather than being open to scientists from across the world. This raises an unavoidable question: if scientific credibility rests on discovery and peer recognition, why should clerical status determine who leads a body that represents astronomy?

The history of Jesuit engagement with astronomy provides some answers. Astronomy has never been pursued in Jesuit hands as a purely neutral science. Instead, it has functioned as an instrument of diplomacy, persuasion, and missionary influence.

In China, during the 17th century, Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci realized that accurate astronomical knowledge could win access to circles otherwise closed to foreigners. His successor Johann Adam Schall von Bell went further, rising to head the Imperial Astronomical Bureau. Historian R. Po-chia Hsia notes that Schall “leveraged his position to embed Jesuit accommodation efforts within official structures.” In effect, astronomy became a ticket to political influence and cultural legitimacy.

In India, a different script unfolded. Maharaja Jai Singh II, an accomplished astronomer himself, invited Jesuits in 1734 to compare his sophisticated calculations with European tables. As historian Dhruv Raina points out, this was “scientific comparison, not dependence.” The balance of authority remained with the Indian ruler. In southern India, however, Jesuits dazzled local communities with eclipse predictions and calendar reforms. Historian Ines Županov interprets these acts as “missionary positioning”—carefully staged performances that enhanced credibility and smoothed the path for conversion.

From Beijing to Pondicherry, the lesson is consistent: astronomy in Jesuit practice was rarely just about exploring the heavens. It was a cultural and political tool.

Father Richard D’Souza’s own journey highlights the tension between priesthood and astrophysics. Born in Goa, he spent his childhood in Kuwait before his family returned as refugees during the Gulf War. He pursued a BSc in Physics, joined the Jesuits in 1996, and was ordained in 2011. Later, he obtained a PhD in Astronomy at the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

In his own words, he insists: “there is no conflict in looking at the universe with both faith and reason.” But this claim invites scrutiny. Biblical cosmology—Genesis describing a dome separating waters above and below, Psalms portraying Earth as immovable, Joshua commanding the sun to stand still, Revelation imagining stars falling to Earth—reflects a worldview formed without telescopes or galaxies. These are not metaphors for black holes or dark matter; they are pre-scientific visions of the cosmos.

For an astrophysicist bound by clerical vows, reconciling such texts with evidence-based science requires more than harmony—it demands selective interpretation. The deeper issue is not whether Father D’Souza personally believes one over the other, but whether the institution he serves allows science to speak with independence when it collides with scripture.

The Observatory’s Dual Role

The Vatican Observatory today performs important work in astrophysics, often collaborating with international scientists. Yet its role is not merely scientific. By placing Jesuit priests with advanced degrees in astronomy at the forefront, the Vatican secures two objectives: it projects itself as a patron of modern science, while ensuring that theology remains the ultimate frame of reference.

This dual role explains why every director must also be a priest. Scientific training alone is not sufficient; obedience to faith is the deciding factor. The structure ensures that discoveries remain aligned with a larger narrative: science may expand knowledge of the universe, but only in ways that do not unsettle the authority of the Church.

Father D’Souza’s appointment is significant not just because he is Indian, but because it reflects continuity. The Church has long sought to rebrand itself as a friend of science, while quietly preserving control over the boundaries of inquiry. Astronomy, with its prestige and wonder, serves as the perfect vehicle for this project.

For India, his rise is being celebrated as proof of intellectual contribution to the global stage. That pride is not misplaced. But the larger context should not be ignored. History shows us that Jesuit astronomy has often been less about universal truths and more about influence—whether in Chinese courts or Indian kingdoms.

The Vatican’s appointment of Father Richard D’Souza has been framed as a milestone of harmony between faith and science. But history teaches caution. From Galileo’s trial to missionary positioning in Asia, the Church has too often used astronomy as a stage for authority rather than discovery.

Father D’Souza’s directorship therefore raises questions not only about stars and galaxies, but about power: who controls the narrative of the universe, and on what terms? What looks like progress may, once again, be strategy—an attempt to cloak theology in the language of science, ensuring that even the cosmos is viewed through the lens of faith.

Source: Vayuveg

Yet behind the applause lie deeper questions. Can the same Church that condemned Galileo, censored Copernicus, and resisted scientific discoveries for centuries now be trusted as the guardian of science? Or does this appointment mark another moment in a long history of presenting theology under the mantle of astronomy, with clerical obedience still placed above free inquiry? What appears as progress may, in fact, be strategy—an old story retold in new language.

Shadows of the Past

The Vatican Observatory has always existed in the tension between faith and evidence. Re-established in 1891 by Pope Leo XIII, it was not born of curiosity alone. Its stated purpose was to “counter accusations of hostility of the Church toward science.” The gesture was defensive, meant to improve the Church’s image at a time when modern science was rapidly distancing itself from dogma.

Since then, almost every director of the Observatory has come from the Jesuit order—Johann Hagen in the early years, later George Coyne, José Gabriel Funes, Guy Consolmagno, and now Father D’Souza. In other words, leadership has been reserved for priests rather than being open to scientists from across the world. This raises an unavoidable question: if scientific credibility rests on discovery and peer recognition, why should clerical status determine who leads a body that represents astronomy?

The Jesuit Strategy: Astronomy as Diplomacy

The history of Jesuit engagement with astronomy provides some answers. Astronomy has never been pursued in Jesuit hands as a purely neutral science. Instead, it has functioned as an instrument of diplomacy, persuasion, and missionary influence.

In China, during the 17th century, Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci realized that accurate astronomical knowledge could win access to circles otherwise closed to foreigners. His successor Johann Adam Schall von Bell went further, rising to head the Imperial Astronomical Bureau. Historian R. Po-chia Hsia notes that Schall “leveraged his position to embed Jesuit accommodation efforts within official structures.” In effect, astronomy became a ticket to political influence and cultural legitimacy.

In India, a different script unfolded. Maharaja Jai Singh II, an accomplished astronomer himself, invited Jesuits in 1734 to compare his sophisticated calculations with European tables. As historian Dhruv Raina points out, this was “scientific comparison, not dependence.” The balance of authority remained with the Indian ruler. In southern India, however, Jesuits dazzled local communities with eclipse predictions and calendar reforms. Historian Ines Županov interprets these acts as “missionary positioning”—carefully staged performances that enhanced credibility and smoothed the path for conversion.

From Beijing to Pondicherry, the lesson is consistent: astronomy in Jesuit practice was rarely just about exploring the heavens. It was a cultural and political tool.

Father D’Souza: Faith First or Science First?

Father Richard D’Souza’s own journey highlights the tension between priesthood and astrophysics. Born in Goa, he spent his childhood in Kuwait before his family returned as refugees during the Gulf War. He pursued a BSc in Physics, joined the Jesuits in 1996, and was ordained in 2011. Later, he obtained a PhD in Astronomy at the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

In his own words, he insists: “there is no conflict in looking at the universe with both faith and reason.” But this claim invites scrutiny. Biblical cosmology—Genesis describing a dome separating waters above and below, Psalms portraying Earth as immovable, Joshua commanding the sun to stand still, Revelation imagining stars falling to Earth—reflects a worldview formed without telescopes or galaxies. These are not metaphors for black holes or dark matter; they are pre-scientific visions of the cosmos.

For an astrophysicist bound by clerical vows, reconciling such texts with evidence-based science requires more than harmony—it demands selective interpretation. The deeper issue is not whether Father D’Souza personally believes one over the other, but whether the institution he serves allows science to speak with independence when it collides with scripture.

The Observatory’s Dual Role

The Vatican Observatory today performs important work in astrophysics, often collaborating with international scientists. Yet its role is not merely scientific. By placing Jesuit priests with advanced degrees in astronomy at the forefront, the Vatican secures two objectives: it projects itself as a patron of modern science, while ensuring that theology remains the ultimate frame of reference.

This dual role explains why every director must also be a priest. Scientific training alone is not sufficient; obedience to faith is the deciding factor. The structure ensures that discoveries remain aligned with a larger narrative: science may expand knowledge of the universe, but only in ways that do not unsettle the authority of the Church.

What Lies Ahead?

Father D’Souza’s appointment is significant not just because he is Indian, but because it reflects continuity. The Church has long sought to rebrand itself as a friend of science, while quietly preserving control over the boundaries of inquiry. Astronomy, with its prestige and wonder, serves as the perfect vehicle for this project.

For India, his rise is being celebrated as proof of intellectual contribution to the global stage. That pride is not misplaced. But the larger context should not be ignored. History shows us that Jesuit astronomy has often been less about universal truths and more about influence—whether in Chinese courts or Indian kingdoms.

The Vatican’s appointment of Father Richard D’Souza has been framed as a milestone of harmony between faith and science. But history teaches caution. From Galileo’s trial to missionary positioning in Asia, the Church has too often used astronomy as a stage for authority rather than discovery.

Father D’Souza’s directorship therefore raises questions not only about stars and galaxies, but about power: who controls the narrative of the universe, and on what terms? What looks like progress may, once again, be strategy—an attempt to cloak theology in the language of science, ensuring that even the cosmos is viewed through the lens of faith.

Source: Vayuveg